Connecting the Dots: The Detective Work of Separating Correlation from Causation

This article is Part II of a five-part series, “Acetaminophen at the Intersection,” exploring how this controversy demonstrates the critical need for rigorous analysis at the crossroads of science, justice, and economics.

In April 2024, JAMA published a groundbreaking study tracking 2.5 million Swedish children born since 1995. Within 48 hours, contradictory headlines flooded news feeds—some proclaimed “Tylenol safe during pregnancy,” while others warned that autism questions remained unresolved. Obstetric hotlines reported a surge in anxious calls from expectant mothers. The study’s critical finding—that autism and ADHD risk disappeared when researchers compared exposed children with their unexposed siblings—demonstrates why correlation is merely a starting point, not definitive proof [1]. Scientists approach potential drug-risk signals like detectives, gathering multiple lines of evidence: measuring drug metabolites in cord blood, comparing siblings, and testing statistics against confounding factors like genetics, fever, and infection. Meanwhile, regulatory bodies and medical organizations maintain their guidance: use acetaminophen when medically necessary, but continue studying the issue.

The Causation Detective’s Toolkit

Epidemiologists approach causal inference as a layered pyramid. Simple correlation studies form the base, while randomized controlled trials—rarely possible in pregnancy research—represent the gold standard at the apex. Between these extremes lie increasingly sophisticated research designs that strengthen confidence in findings:

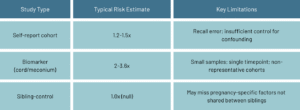

- Prospective cohorts follow thousands of pregnant individuals and their children, recording medication use before outcomes occur. This establishes temporal order (exposure precedes outcome) but remains vulnerable to hidden biases.

- Biomarker studies measure acetaminophen metabolites in cord blood or meconium, providing objective exposure data rather than relying on self-reporting. However, these typically capture only a snapshot of pregnancy exposure [2].

- Sibling-control studies compare brothers and sisters with different exposure histories, effectively neutralizing shared genetic and household factors. A 2024 Swedish analysis of 1.8 million sibling pairs effectively eliminated the modest autism and ADHD signals observed in the general population cohort [1].

- Negative-control and Mendelian-randomization analyses serve as scientific reality checks, testing whether associations persist in contexts where biological mechanisms don’t support causation, or examining whether genetic variants tied to acetaminophen metabolism predict neurodevelopmental outcomes [3].

Together, these methods allow researchers to ascend the “causation pyramid,” systematically ruling in or out alternative explanations for observed associations.

The Confounding Conundrum

Correlation’s fundamental challenge is that a third factor may drive both exposure and outcome. For acetaminophen and neurodevelopmental disorders, three major confounders demand attention:

- Familial genetics. ASD and ADHD are highly heritable—74-80% of risk originates in DNA [4]. Parents carrying these genetic variants may experience more migraines, chronic pain, or autoimmune flares that prompt increased acetaminophen use.

- Indication bias. Fever and infection during pregnancy can themselves raise neurodevelopmental risk. The fever or illness—not the medication treating it—could be the actual culprit.

- Socio-environmental factors. Smoking, obesity, or socioeconomic stress correlate with both higher over-the-counter analgesic use and developmental challenges.

When the landmark Swedish sibling study controlled for shared genetics and household environment, the hazard ratio for autism plummeted from 1.05 to 0.98—essentially erasing the association [1]. In contrast, meta-analyses without such rigorous controls still report approximately 30% elevated risk, underscoring how methodology substantially influences conclusions [5].

Science vs. Headlines

Media coverage often simplifies complex findings into attention-grabbing statements like “Tylenol doubles autism risk.” The actual research tells a more nuanced story [2]:

Journalists seek compelling narratives with clear villains, while researchers deal in probability and uncertainty. Responsible science communication requires explaining effect sizes, confidence intervals, and why methodologically stronger studies (like sibling comparisons) may outweigh more dramatic but less rigorous findings.

When Good Science Meets Bad Communication

The 2021 Bauer et al. Nature Reviews “consensus statement” urged pregnant women to limit acetaminophen use [6]. Professional organizations including ACOG and SMFM responded that evidence remained inconclusive and that untreated fever or pain poses demonstrable risks [7]. This clash highlights three communication pitfalls:

- Overstating certainty: Calling for warnings before causal criteria are met undermines public trust when later studies contradict early signals.

- Ignoring trade-offs: NSAIDs, often suggested as alternatives, carry documented third-trimester risks. While safer options exist for pain management (physical therapy, mindfulness), none match acetaminophen’s effectiveness against fever [9].

- Confusing correlation with causation: Headlines that omit discussion of confounding factors invite misinterpretation and fuel litigation rather than informed choice.

In Plain English

Scientists use multiple approaches—long-term studies, biomarkers, and sibling comparisons—to determine whether prenatal acetaminophen exposure causes autism or ADHD, or whether other factors explain the connection. Early studies found small risk increases, but a comprehensive Swedish study comparing siblings found no effect once shared genetics and home environment were considered [1]. Medical organizations therefore maintain that acetaminophen remains the safest medication for fever or pain during pregnancy, recommending it be used sparingly and at the lowest effective dose [7].

Myth vs. Reality

- Myth: “Any Tylenol during pregnancy doubles autism risk.”

Reality: Large sibling studies show no increased risk when family factors are properly controlled [1]. - Myth: “Fever is safer than acetaminophen.”

Reality: Untreated high fever has documented links to birth defects and developmental issues [8]. - Myth: “There are proven acetaminophen alternatives with zero risks.”

Reality: All pain relievers involve trade-offs; NSAIDs can harm fetal circulation in late pregnancy [9].

Key Takeaway

The strongest current evidence indicates that familial and health factors—not acetaminophen itself—explain most reported links to autism and ADHD. Methodology matters: studies that control for genetics and confounding factors consistently show weaker or non-existent associations than those that don’t [1][5].

Coming Next

In Part III, “When Science Stands Trial,” we’ll step inside the courtroom where scientific nuance meets legal strategy, examining how courts evaluate complex and sometimes contradictory scientific evidence.

References

- Ahlqvist VH, et al. Acetaminophen use during pregnancy and children’s risk of autism, ADHD, and intellectual disability. JAMA. 2024.

- Ji Y, et al. Association of cord plasma biomarkers of in utero acetaminophen exposure with risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019.

- Baker B, et al. Association of prenatal acetaminophen exposure measured in meconium with risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder mediated by frontoparietal network brain connectivity. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020.

- Sandin S, et al. The heritability of autism spectrum disorder. JAMA. 2017.

- Masarwa R, et al. Prenatal exposure to acetaminophen and risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression analysis of cohort studies. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2018;187(8):1817-1827.

- Bauer AZ, et al. Paracetamol use during pregnancy — A call for precautionary action. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2021.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG response to consensus statement on paracetamol use during pregnancy. 2021.

- Sass L, et al. Fever in pregnancy and the risk of congenital malformations: A cohort study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2017.

- NSAIDs: Drug Safety Communication – Avoid use of NSAIDs in pregnancy at 20 weeks or later. October 2020.